- VetSummary.com

- Posts

- Heartworm Meds Safe For Eyes?

Heartworm Meds Safe For Eyes?

Volume 24 Issue 5

Hello Summarians!

One of the things that fascinates me about putting together this newsletter is the “niche” knowledge that comes with specific specialties. I knew the lactones could cause some issues, but I did not put together the specific concerns about the eye. It’s good to know that teams are out there refining their craft and contributing to the knowledge base.

Please tell people about Vet Summary — we need your support.

Lactones Eye Safety

Macrocyclic lactones are medications commonly used to prevent and treat parasites in dogs, especially heartworm disease. Although these drugs are generally very safe, side effects can occur, particularly at high doses or in dogs with a genetic mutation (MDR-1/ABCB1) that affects drug clearance from the brain and nervous system. In overdose situations, these drugs can cause neurologic and eye-related signs such as dilated pupils, vision loss, and reduced retinal electrical activity measured by electroretinography (ERG). Because sudden acquired retinal degeneration syndrome (SARDS) also causes sudden blindness with extinguished ERG responses, there has been speculation that routine heartworm preventatives might contribute to SARDS.

This study evaluated whether normal, monthly oral doses of macrocyclic lactones cause retinal or pupil-related side effects in healthy adult dogs. Using both retrospective data and a prospective study design, researchers assessed retinal function with ERG testing and pupil responses with chromatic pupillary light reflex (PLR) testing. The results showed no significant differences in ERG measurements between dogs receiving routine heartworm preventatives and those not receiving them. When ERGs were performed near the time of peak drug levels in the blood—when side effects would be most likely—no retinal dysfunction was detected.

A small number of dogs showed mildly reduced pupil constriction in response to red light after medication administration, but these changes were inconsistent and not supported by ERG findings. Because PLR testing is known to vary between tests, these small differences were most likely due to normal test variability rather than true retinal damage. Importantly, retinal toxicity reported in the literature has occurred only with overdoses that were many times higher than preventive doses, and vision typically recovered with treatment, unlike SARDS, which causes permanent blindness.

The study also compared the risk of medication side effects with the risk of heartworm disease. Heartworm infection is far more common than SARDS and can cause severe, sometimes fatal heart and lung disease. Given the lack of evidence for retinal harm from routine preventatives and the serious consequences of heartworm infection, the benefits of regular heartworm prevention clearly outweigh the small risk of side effects.

The authors note several limitations, including a relatively small sample size and the inability to detect very subtle changes in retinal function. However, even if such minor changes exist, they are unlikely to be clinically meaningful or related to SARDS. Overall, the findings strongly support the continued routine use of oral heartworm preventatives in dogs.

R. G. Hopper, A. L. Ludwig, M. M. Salzman, et al., “ Effects of Oral Macrocyclic Lactone Heartworm Preventatives on Retinal Function and Chromatic Pupillary Light Reflex in Healthy Companion Dogs,” Veterinary Ophthalmology 29, no. 1 (2026): e13319, https://doi.org/10.1111/vop.13319.

Bottom line — They are safe.

Treatment Duration For Pneumonia

Since antibiotics were first introduced, long treatment courses were traditionally recommended because of concerns about treatment failure or relapse. However, many recent studies in both human and veterinary medicine now show that shorter antibiotic courses can be just as effective for many infections, while also reducing side effects, cost, and the risk of antibiotic resistance. In human medicine, pneumonia is commonly treated for only 3 to 7 days, and doctors are advised not to rely on chest X-rays to decide when to stop treatment because radiographic changes often improve more slowly than clinical signs. Historically, veterinary medicine recommended much longer courses—often 3 to 6 weeks—for dogs and cats with pneumonia, usually continuing antibiotics until radiographs had fully resolved. More recent international veterinary guidelines now suggest reassessing patients after 10 to 14 days and stopping treatment if they are clinically improving, although strong evidence has been lacking.

To address this gap, the authors performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine whether shorter antibiotic durations are as effective as longer ones for treating bacterial pneumonia in dogs and cats. They searched four major scientific databases from their start through April 2025 and followed established PRISMA guidelines. Studies were included if they involved dogs or cats with suspected or confirmed bacterial pneumonia and reported treatment duration and outcomes such as clinical improvement, radiographic resolution, recurrence, or death. Both randomized trials and observational studies were included because of the limited available evidence.

Out of more than 2,200 studies screened, only three met the inclusion criteria. All three involved dogs; no studies in cats were found. Together, these studies included 74 dogs and compared shorter antibiotic courses (about 10 to 14 days) with longer courses (about 21 to 28 days). Across studies, there was no meaningful difference in recovery rates at four weeks between dogs treated with shorter versus longer antibiotic durations. There were also no clear differences in recurrence rates or radiographic improvement. However, the confidence in these findings was low because the studies were small, used different methods, and sometimes relied on radiographs rather than clinical signs to define recovery.

Overall, the review suggests that shorter antibiotic courses appear to be as effective as longer ones for treating pneumonia in dogs, supporting current veterinary guidelines that encourage shorter, clinically guided treatment. However, the evidence is still very limited. Importantly, no studies evaluated antibiotic courses shorter than 10 days, meaning it remains unknown whether even shorter treatments—similar to those used in humans—would be safe and effective in dogs or cats. Larger, high-quality studies, especially including cats and testing courses under 7 days, are needed to better guide veterinary practice and reduce unnecessary antibiotic use.

Emdin, F., Emdin, A., Ong, S. W. X., Leung, V., Schwartz, K. L., Langford, B. J., Brown, K. A., Weese, J. S., Massarella, S., & Daneman, N. (2026). Shorter versus longer durations of antibiotic treatment for pneumonia in dogs and cats: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.25.09.0588

Bottom line — Shorter courses appear to be as effective as longer ones.

Genetic screening for canine olfactory ability

Equine ulcerative keratomycosis is a serious fungal infection of the cornea that can threaten vision and even the eye itself. Treatment often requires very frequent antifungal eye drops for long periods of time and sometimes surgery, which can be difficult for owners to keep up with and expensive. Because fungal identification and drug susceptibility testing can take time, antifungal drugs may not always be available or work well in the eye, and resistance is an increasing concern, there is strong interest in new add-on treatments that could reduce the overall treatment burden while improving outcomes.

This study tested whether ultraviolet C (UV-C) light could help inactivate the main types of molds commonly involved in equine keratomycosis, especially Aspergillus and Fusarium. UV-C light can kill microorganisms by damaging their genetic material and other important cell components, which stops them from reproducing. Unlike antibiotics and antifungals, UV-C does not appear to drive classic drug resistance. However, UV-C can also harm living tissue, so the key question is whether a “low enough” dose could still reduce fungal growth while staying within a range that might be safe for the cornea.

Researchers used an affordable handheld LED UV-C device with a peak wavelength of 275 nm. The device was modified with a small collimator tip to make the beam more even and predictable. They confirmed the wavelength and measured the beam intensity at different distances. They then spread known concentrations of four fungal isolates (two Aspergillus species and two Fusarium species) onto agar plates and exposed the center of the plates to UV-C using different distances and exposure times. They tested three protocols: a 10 mm distance with single exposures of 5, 15, or 30 seconds; a 15 mm distance with single exposures of 10 or 15 seconds and also repeated exposures (a second treatment 4 hours later); and a 20 mm distance with similar single and repeated exposures. After exposure, plates were incubated and evaluated at 24, 48, and 72 hours. The team measured the surface area of the clear “inhibition zone” where fungal growth was suppressed, examined the zones under a microscope, and checked for regrowth by swabbing the treated center and culturing it again.

Overall, UV-C exposure created a clear zone of reduced fungal growth for every fungal isolate and every treatment condition, while control plates had no inhibition at all. Longer exposure times usually produced larger inhibition zones, and repeating the exposure (two treatments separated by 4 hours) produced the largest inhibition zones. Even though the inhibition zone tended to shrink over time as fungus from the edges grew inward, the treated plates still consistently showed significantly less growth than controls at all time points. Under the microscope, the treated center lacked the dense, thick mat of fungal filaments seen in untreated areas, although some scattered fungal elements could still be found in parts of the inhibition zone, especially closer to the transition edge.

When the team looked at whether fungus could regrow from the treated center, they found that short single exposures often reduced growth but did not eliminate it. At 10 mm, regrowth happened in all plates treated for 5 or 15 seconds, and regrowth was still present in many plates even after 30 seconds, though a few plates—especially some Fusarium plates—showed no regrowth. With the 15 mm and 20 mm protocols, repeated 15-second exposures came closest to eliminating regrowth, but most plates still had at least some regrowth. This supports the idea that molds, which have more complex multicellular structures than bacteria or yeast, may require higher or more repeated UV-C dosing for complete inactivation.

A practical reason the researchers tested different distances is that, in a real horse, holding a device at a perfectly fixed distance from the cornea may be hard, especially in an awake patient. As the distance increases, the light spreads out and intensity drops, which reduces the dose delivered to any one area. Interestingly, a single 15-second exposure still produced meaningful inhibition at all tested distances, and the study did not find a major difference in inhibition zone size across distances for that single 15-second exposure. However, regrowth appeared worse at longer distances, likely because the delivered dose per area was lower and the beam intensity fades toward the edges. Repeated exposures at 20 mm produced very large inhibition zones, probably because the spot size was larger and the total delivered dose across two exposures approached the dose delivered by a single closer exposure.

The authors conclude that this affordable 275 nm UV-C device can inhibit Aspergillus and Fusarium molds in vitro, and that a single 15-second exposure at about 10 mm distance (estimated 22.5 mJ/cm²) may be a reasonable “best compromise” between antifungal effect and likely corneal safety based on safety data from other UV-C wavelengths. At the same time, they emphasize that true safety data for 275 nm on equine corneal tissue are not yet available. Before this could be used clinically, studies are needed to determine how deeply 275 nm UV-C penetrates the equine cornea, whether it causes harmful DNA changes like cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, and whether it could safely help in real infections, including deeper stromal fungal abscesses. In short, the results are promising as a first step, but more preclinical and clinical testing is required to confirm both safety and real-world effectiveness in horses.

M. Hoerdemann, D. K. Sahoo, R. A. Allbaugh, and M. A. Kubai, “ Ultraviolet C (UV-C) Light Therapy for Equine Ulcerative Keratomycosis—An In Vitro Study,” Veterinary Ophthalmology 29, no. 1 (2026): e70012, https://doi.org/10.1111/vop.70012.

Bottom line — Impressive first steps. More research is needed.

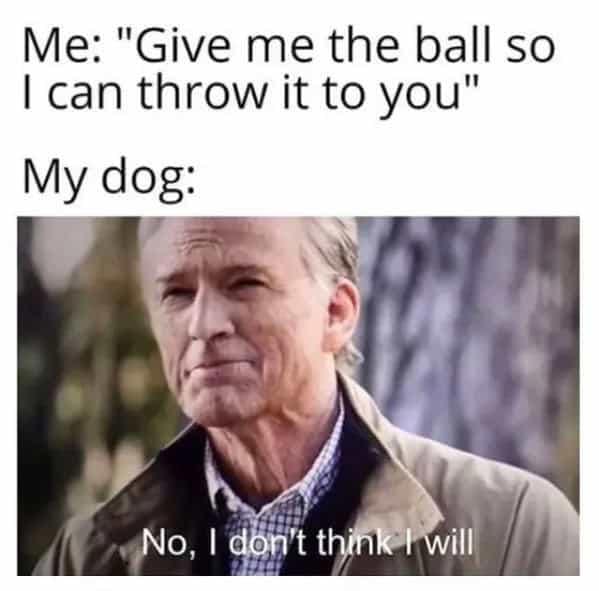

Just putting things in perspective …

Reply